Films containing computer-generated images and computer animation have given birth not only to its own unique aesthetics, but also a critique of its visual seductiveness and dominance. In addressing this so-called ‘spectacular realism’ (Lister 2003: 145), we are faced with two main connotations of the spectacle. First, it’s the ability to distract the attention of the audience from the narrative; and second, it’s the commodification of social life. In Guy Debord’s book, The Society of the Spectacle, he asserts that our vision itself of the world is commodified: the world that we see is a world transformed largely by post-war capitalism — an illusion and a masking, of real life. (Listers 2003: 145) We are more likely to see — and look — at the appearance of things, not at their underlying relationships. This characteristic of today’s society is reflected in the way marketing and advertising weave their magic. The proliferation of branded communities — though I believe not just to be a product of commercial forces — is certainly a testimony to this. The way brands have become synonymous to lifestyles, choices and frame of mind seems to reinforce Debord’s notions of the society of the spectacle.

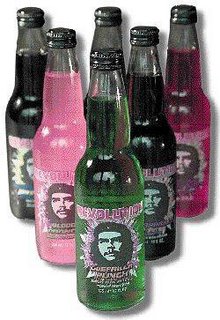

It’s not just they way we are fascinated with the CGI’s employed in today’s films. This fascination (or blind admiration)— the ‘centred eye’ of Albertian perspective — actually extends outside the cinema. The way we see the world is like looking through the camera lens that captures only the surface of things. The fascination for the spectacular extends to the way we label our environment and experiences in terms of products and brands: in terms of images purported by the current dominant institutions in society. Look at the way we have commodified Che Guevara, who has now become a brand himself. But of what? Of many things except the Revolution. What activists used to have as a symbol of resistance has now been assimilated by big business. Many of the so-called new ‘political’ ads, which supposedly resist discrimination and promote freedom and equality, or the emancipation of women, lose in the long run, the politics of their message. (The new ad campaign of Libresse sanitary napkins in the Netherlands is an example of this…but that’s for a later blog – timi). There’s always the danger that these radical and counter-culture statements can be reduced to mere hype and advertising gimmicks.

This is not to say that counter-culture has not achieved anything, but a statement of how the commodity-driven society continuously assimilates the successes of counter-culture. I’m saying that political ads might have originally possessed the radical potential, but their message was later lost in the glamour of advertising. What big business does is to use political messages (images), but filter out the politics. They’ve taken away the politics in the struggle for these freedoms. They’ve commodified Che.

Leave a Reply